Fish Guide

Lamprey

|

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia, by MultiMedia |

| Lamprey | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sea lamprey from Sweden

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

Geotriinae Mordaciinae Petromyzontinae |

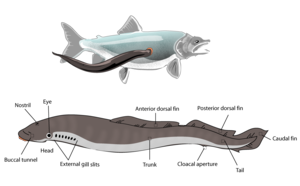

A lamprey (sometimes also called lamprey eel) is a jawless fish with a toothed, funnel-like sucking mouth, with which most species bore into the flesh of other fish to suck their blood. In zoology, lampreys are often not considered to be true fish because of their vastly different morphology and physiology.

Contents |

Physical description

Lampreys live mostly in coastal and fresh waters, although at least one species, Geotria australis, probably travels significant distances in the open ocean, as is evidenced by the lack of reproductive isolation between Australian and New Zealand populations, and the capture of a specimen in the Southern Ocean between Australia and Antarctica. They are found in most temperate regions except Africa. Their larvae have a low tolerance for high water temperatures, which is probably the reason that they are not found in the tropics. Outwardly resembling eels in that they have no scales, an adult lamprey can range anywhere from 13 to 100 centimetres (5 to 40 inches) long. Lampreys have one or two dorsal fins, large eyes, one nostril on the top of their head, and seven gills on each side. The unique morphological characteristics of lampreys, such as their cartilaginous skeleton, means that they are the sister taxon (see cladistics) of all living jawed vertebrates (gnathostomes) and are not classified within the Vertebrata itself. The hagfish, which superficially resembles the lamprey, is the sister taxon of the lampreys and gnathostomes (a clade termed the Craniata).

Lampreys begin life as burrowing freshwater larvae (ammocoetes). At this stage, they are toothless, have rudimentary eyes, and feed on microorganisms. This larval stage can last five to seven years and hence was originally thought to be an independent organism. After these five to seven years, they transform into adults in a metamorphosis which is at least as radical as that seen in amphibians, and which involves a radical rearrangement of internal organs, development of eyes and transformation from a mud-dwelling filter feeder into an efficient swimming predator, which typically moves into the sea to begin a predatory/parasitic life, attaching to a fish by their mouths, secreting an anticoagulant to the host, and feeding on the blood and tissues of the host. In most species this phase lasts about 18 months. Whether lampreys are predators or parasites is a blurred question.

Not all lampreys can be found in the sea. Some lampreys are landlocked and remain in fresh water, and some of these stop feeding altogether as soon as they have left the larval stage. The landlocked species are usually rather small.

To reproduce, lampreys return to fresh water (if they left it), build a nest, then spawn, that is, lay their eggs or excrete their semen, and then invariably die. In Geotria australis, the time between ceasing to feed at sea and spawning can be up to 18 months long.

Recent studies reported in Nature suggest that lampreys have evolved a unique type of immune system with parts that are unrelated to the antibodies found in mammals. They also have a very high tolerance to iron overload, and have evolved biochemical defenses to detoxify this metal.

Fossil lampreys

Lamprey fossils are exceedingly rare; cartilage does not fossilize as readily as bone. Until 2006, the oldest known fossil lampreys were from Early Carboniferous limestones[1], laid down in marine sediments in North America: Mayomyzon pieckoensis and Hardistiella montanensis. In the 22 June 2006 issue of Nature, Mee-mann Chang and colleagues reported on a fossil lamprey from the same Early Cretaceous lagerstätten that have yielded feathered dinosaurs, in the Yixian Formation of Inner Mongolia. The new species, morphologically similar to Carboniferous and modern forms, was given the name Mesomyzon mengae ("Middle lamprey"). The exceedingly well-preserved fossil showed a well-developed sucking oral disk, a relatively long branchial apparatus showing branchial basket, seven gill pouches, gill arches and even the impressions of gill filaments, as well as about 80 myomeres of its musculature.

A few months later, in the 27 October issue of Nature, an even older fossil lamprey, dated 360 Mya, was reported from Witteberg Group rocks near Grahamstown, in the Eastern Cape of South Africa. This species, dubbed Priscomyzon riniensis still strongly resembled modern lampreys despite its Devonian age.

Taxonomy

The taxonomy presented here is that given by Fisher, 1994. This work classifies lampreys as the sole living members of the class Cephalaspidomorphi.[2] The lampreys entail the single order Petromyzontiformes and family Petromyzontidae.[3]

Within this family, there are 40 recorded species in nine genera and three subfamilies:

- Subfamily

Geotriinae

- Genus

Geotria

- Geotria australis (Gray,1851)

- Genus

Geotria

- Subfamily

Mordaciinae

- Genus

Mordacia

- Mordacia lapicida (Gray, 1851)

Mordacia mordax (Richardson, 1846)

Mordacia praecox (Potter, 1968)

- Mordacia lapicida (Gray, 1851)

- Genus

Mordacia

- Subfamily

Petromyzontinae

- Genus

Caspiomyzon

- Caspiomyzon wagneri (Kessler, 1870)

- Genus

Eudontomyzon

- Eudontomyzon danfordi (Regan, 1911)

Eudontomyzon hellenicus (Vladykov, Renaud, Kott and Economidis, 1982)

Eudontomyzon mariae (Berg, 1931)

Eudontomyzon morii (Berg, 1931)

Eudontomyzon stankokaramani (Karaman, 1974)

Eudontomyzon vladykovi (Oliva and Zanandrea, 1959)

- Eudontomyzon danfordi (Regan, 1911)

- Genus

Ichthyomyzon

- Ichthyomyzon bdellium (Jordan, 1885) - Ohio

lamprey

Ichthyomyzon castaneus Girard, 1858 - chestnut lamprey

Ichthyomyzon fossor (Reighard and Cummins, 1916) - northern brook lamprey

Ichthyomyzon gagei (Hubbs and Trautman, 1937) - southern brook lamprey

Ichthyomyzon greeleyi (Hubbs and Trautman, 1937) - mountain brook lamprey

Ichthyomyzon unicuspis (Hubbs and Trautman, 1937) - silver lamprey

- Ichthyomyzon bdellium (Jordan, 1885) - Ohio

lamprey

- Genus

Lampetra

- Lampetra aepyptera (Abbott, 1860) - least

brook lamprey

Lampetra alaskensis (Vladykov and Kott, 1978)

Lampetra appendix (DeKay, 1842) - American brook lamprey

Lampetra ayresii (Günther, 1870)

Lampetra fluviatilis (Linnaeus, 1758)

Lampetra hubbsi (Vladykov and Kott, 1976) - Kern brook lamprey

Lampetra lamottei (Lesueur, 1827)

Lampetra lanceolata (Kux and Steiner, 1972)

Lampetra lethophaga (Hubbs, 1971) - Pit-Klamath brook lamprey

Lampetra macrostoma (Beamish, 1982) - Vancouver lamprey

Lampetra minima (Bond and Kan, 1973) - Miller Lake lamprey

Lampetra planeri (Bloch, 1784)

Lampetra richardsoni (Vladykov and Follett, 1965) - western brook lamprey

Lampetra similis (Vladykov and Kott, 1979) - Klamath lamprey

Lampetra tridentata (Richardson, 1836) - Pacific lamprey

- Lampetra aepyptera (Abbott, 1860) - least

brook lamprey

- Genus

Lethenteron

- Lethenteron camtschaticum (Tilesius, 1811)

Lethenteron japonicum (Martens, 1868)

Lethenteron kessleri (Anikin, 1905)

Lethenteron matsubarai (Vladykov and Kott, 1978)

Lethenteron reissneri (Dybowski, 1869)

Lethenteron zanandreai (Vladykov, 1955)

- Lethenteron camtschaticum (Tilesius, 1811)

- Genus

Petromyzon

- Petromyzon marinus (Linnaeus, 1758) - sea lamprey

- Genus

Tetrapleurodon

- Tetrapleurodon geminis (Alvarez, 1964)

Tetrapleurodon spadiceus (Bean, 1887)

- Tetrapleurodon geminis (Alvarez, 1964)

- Genus

Caspiomyzon

Relation to humans

Lampreys have long been used as food for humans. During the Middle Ages, they were widely eaten by the upper classes throughout Europe, especially during fasting periods, since their taste is much meatier than that of most true fish. King Henry I of England is said to have died from eating "a surfeit of lampreys" [1].

Especially in Southwestern Europe (Portugal, Spain, France) they are still a highly prized delicacy. Overfishing has reduced their number in those parts. Lampreys are also consumed in South Korea.

On the other hand, lampreys have become a major plague in the North American Great Lakes after artificial canals allowed their entry during the early 20th century. They are considered an invasive species, have no natural enemies in the lakes and prey on many species of commercial value, such as lake trout. Since the majority of North American consumers, unlike Europeans, refuse to accept lampreys as food fish, the Great Lakes fishery has been very adversely affected by their invasion. They are now fought mostly in the streams that feed the lakes, with special barriers and poisons called lampricides, which are harmless to most other aquatic species. However those programs are complicated and expensive, and they do not eradicate the lampreys from the lakes but merely keep them in check. New programs are being developed including the use of sterilization of male lamprey by trapping of prespawn adults. Research is currently under way on the use of pheromones and how they may be used to disrupt the life cycle (Sorensen, et al., 2005). Control of sea lampreys in the Great Lakes is conducted by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans. The work is coordinated by the Great Lakes Fishery Commission.

Trivia

Vedius Pollio

Vedius Pollio was punished by Augustus for attempting to feed a clumsy slave to the lampreys in his fishpond.

- ...one of his slaves had broken a crystal cup. Vedius ordered him to be seized and to be put to death in an unusual way. He ordered him to be thrown to the huge lampreys which he had in his fish pond. Who would not think he did this for display? Yet it was out of cruelty. The boy slipped from the captor’s hands and fled to Caesar’s feet asking nothing else other than a different way to die—he did not want to be eaten. Caesar was moved by the novelty of the cruelty and ordered him to be released, all the crystal cups to be broken before his eyes, and the fish pond to be filled in... – Seneca, On Anger, III, 40 [2]

Philip Larkin

Christopher Warner, a character in Philip Larkin's early novel Jill is said to have attended a fictional minor public school called Lamprey College.

King Henry I

Henry I of England was said to have died from eating too many lampreys, of which he was fond of eating [3].

Notes

- ^ From the Mississippian Mazon Creek lagerstätte and the Bear Gulch Limestone sequence.

- ^ Cephalaspidomorpha is sometimes given as a subclass of the Cephalaspidomorphi.

- ^ Petromyzoniformes and Petromyzonidae are sometimes used as alternative spellings for Petromyzontiformes and Petromyzontidae respectively.

References

- Mee-mann Chang et al. (2006). "A lamprey from the Cretaceous Jehol biota of China". Nature 441: 972-974 (22 June 2006).

- Sorensen, P; Fine, J; Dvornikovs, V; Jeffrey, C; Shao, F; Wang, J; Vrieze, L; Anderson, K; Hoye, T. (2005). Mixture of new sulfated steroids functions as a migratory pheromone in the sea lamprey. Nature Chemical Biology 1 (November): 324-328.

- Fisher (1994). Fishes of the World, Third Edition. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0-471-54713-1.

- Gess, Robert W.; Coates, Michael I.; Rubidge, Bruce S. (2006). A lamprey from the Devonian period of South Africa. Nature 443: 981-984.

External links

Fish Guide, made by MultiMedia | Free content and software

This guide is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. It uses material from the Wikipedia.